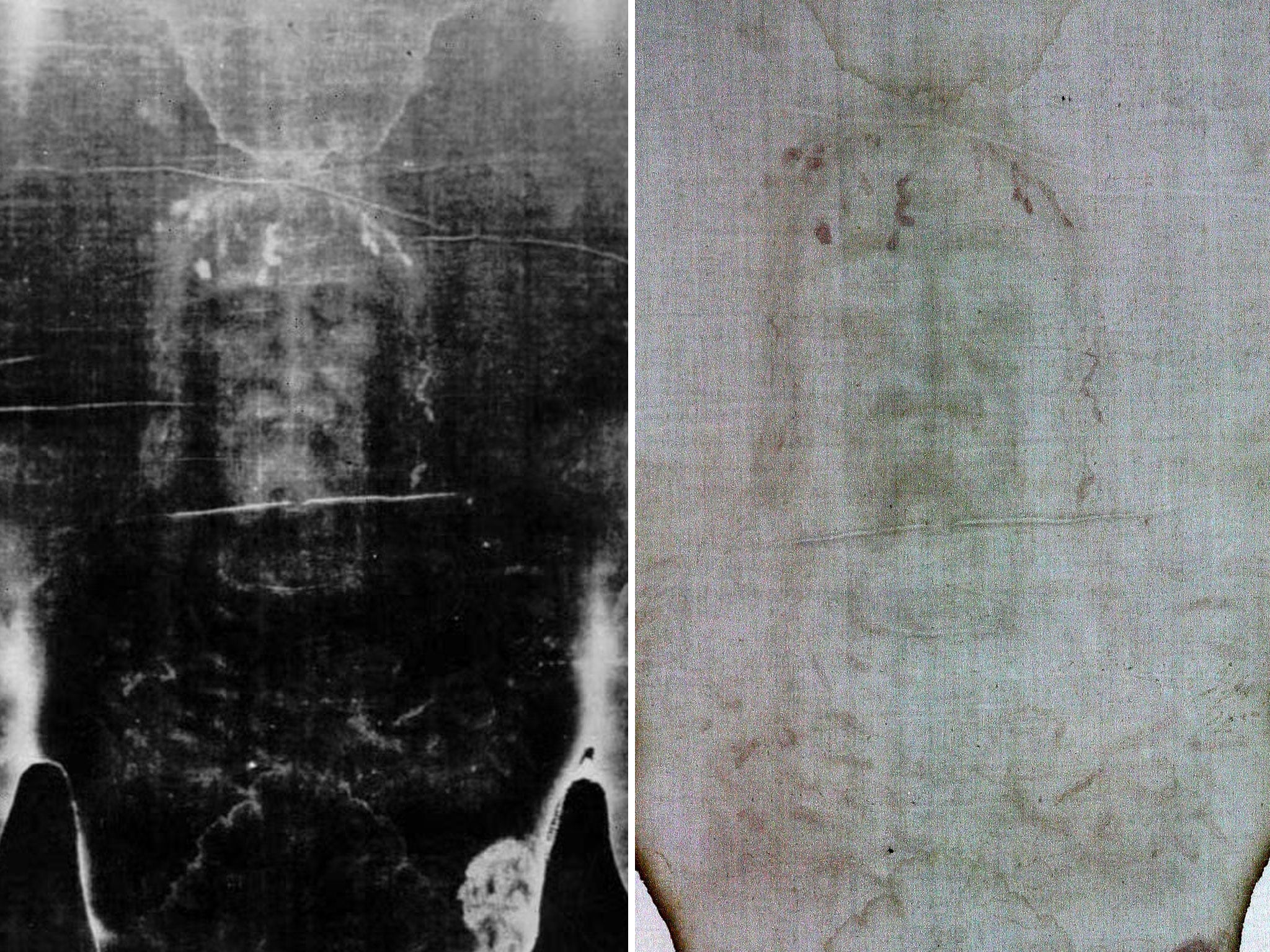

I know skeptics are going to doubt all of that too, because that’s their attitude, but the material that the shroud was made of is very high-quality linen. If you’re trying to make the case for authenticity to a skeptic, what would you mention first? Is there one piece of information that you find powerfully conclusive? So I consider that a very strong indication that the shroud is much older than the carbon-dating test could ever tell us. We have found pollens on the shroud that are not only from France, where it was for many centuries, but pollens from Jerusalem. How do we know that? Because there is also pollen analysis. It’s my conviction that it came from Jerusalem. So we get farther and farther away from this carbon dating.

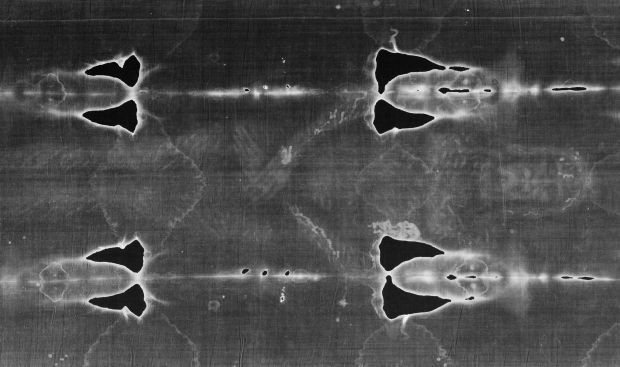

We have records that it came to Constantinople from Edessa, so we know that it was already there in 544. We also know that the shroud was in Constantinople in 1204, which is already before the dating of the carbon tests. We have historical records that the shroud was only moved to Turin in 1578. And besides, we have so much very convincing evidence that the shroud is much older. So that strip has a lot of contamination from their fingers and bacteria, and all of those influence the reading of your carbon dating. We have drawings and pictures showing bishops and priests holding the shroud horizontally from the top. It was taken from the side strip, which is the place that was handled in the past to show the shroud. Another reason was that there was supposed to be testing by seven laboratories, and they ended up with only three of them, and that makes it already more difficult to claim they have scientific information because scientific information has to be reproducible. That’s why they finally put it in a bulletproof case controlled for temperature and other things that could damage it. It’s the document that they have, and that document cannot be damaged. I cannot completely blame the scientists for that because the Vatican is very careful with the shroud. One of the problems with the carbon dating is that the samples were taken from the worst spot on the shroud. There are many reasons, and I discuss them in the book, but I want to be brief here. Why shouldn’t we trust the carbon dating? We have many other indications that the shroud is much older than they have claimed. The data were released, and that gave me the energy to start my research all over again to show that the carbon dating cannot be true. You’re hiding something.” And finally, 30 years later, they won that battle. So, finally, they sued the people who came up with that analysis and said, “You haven’t given us all the data. They had so many indications that the thing was much older. I could not believe that because I knew that carbon dating has a number of pitfalls, and the group that was in favor of the shroud, most of them scientists, could not believe it either. The big bummer came in 1988, when so-called scientists claimed that the shroud could not be older than the 1260s. What drew you to Shroud of Turin research? McDonald discussed these issues with Verschuuren. Subsequent analysis of this data and comparison with the original report led Casabianca’s team to conclude that “homogeneity is lacking in the data and that the procedure should be reconsidered,” casting doubt in the results of the carbon-14 date. Withheld for decades by the British Museum, the raw data was only released in 2017, following a freedom-of-information request by French researcher Tristan Casabianca. One of his reasons for reconsidering the evidence at this time was the availability of the raw data of the carbon-14 tests first reported in 1988. In this book, Verschuuren considers the evidence for and against the authenticity of the shroud from the twin perspective of science and faith.

He now lives in New Hampshire and is using his retirement to write books about the faith and science, among them Aquinas and Modern Science, The Myth of an Anti-Science Church, In the Beginning: How God Made Earth Our Home and, most recently, A Catholic Scientist Champions the Shroud of Turin (Sophia Institute Press, 192 pages, $17.95). His wide-ranging background includes genetics, biological anthropology and statistics, but he was also awarded a doctorate in the philosophy of science, and has taught everything from the philosophy of biology to human genetics to computer programming at universities in America and Europe. Gerard Verschuuren is a Catholic biologist and philosopher who works at the junction of science and religion.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)